An exercise in probability

The following problem is given

A particle is placed uniformly at one of the nine points in a $3\times3$ square grid. The particle then performs a random walk such that at each step one of the adjacent points (to the right or left, upwards or downwards) is chosen with equal probabilities. This means that the particle never remains in a point or moves diagonally.

The question is to find the probability that the particle after three steps is at the central point.

Now, the standard way to approach the problem would be to consider all possible combinations to reach

the center point, compute their probabilities and summing them, since each one corresponds to a different

outcome of a random experiment.

This leads naturally to a series of matrix multiplications.

Here I will use the notation used to describe Markov processes, of which this is a basic example.

Just to give you an idea, a Markov process is when you have a system that evolves, in a probabilistic

way, based on the current position, or current state, independently from the positions (states) assumed

in the past.

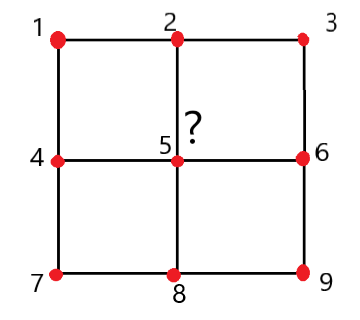

I will call $P$ the transition matrix,

that is the matrix whose element $p_{ij}$ represents the probability for the particle of moving from

state $i$ to state $j$; here I will enumerate the states

by row, as shown in the picture above; as an example, $p_{12}$ is $\frac{1}{2}$ since from state $1$ the particle

can only move to state $4$ or state $2$.

To find the probability of being in state $5$ after three steps the matrix $P^3$ shall be computed; this matrix is the transition

matrix after three steps. The answer to our problem is found by multiplying the row vector of elements all equal to $\frac{1}{9}$ for

the column number five of the

matrix. Performing this algebraic computation in any software gives as result $\frac{4}{27}$.

Let’s now move to the interesting part, and pose ourself this question:

are we able, through abstract thinking, to transform the problem

in a simpler one? If you think about it, the answer is yes.

In the previous computation, we considered all the points as disctinct states of a Markov chain (a Markov

chain is just a Markov process evolving on a discrete time, usually the natural numbers, like in this case).

But the symmetry of the problem might suggest us that the point that lies in the top-left corner is not

different from the point that lies in the bottom-right corner. An analogous consideration can be done

for the top-middle and middle-left points and so on.

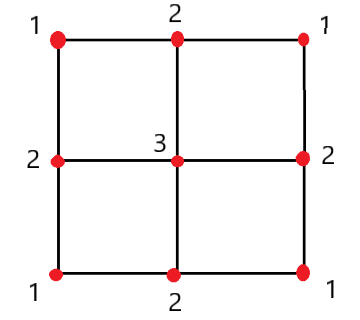

So the idea is to pass from a Markov chain with nine states to a Markov chain with just three states;

I will refer to this states as abstract states, and will enumerate them like in the following picture

You might wonder if the two representations are equivalent or not, so let’s give it some more thoughts.

When the particle lies in the vertices (abstract state $1$), it can

only move to a point belonging to abstract state $2$ . Similarly, when it

is in abstract state $2$, it will have $\frac{1}{3}$ chances to move to abstract state $3$

and $\frac{2}{3}$chances to move to abstract state $1$.

Finally, when particle lies in the center, it will necessarily move to abstract state $2$.

It is clear that, if we are interested only in the probability of ending up in abstract state $3$, the exact

state of the possible nine does not matter, but it is only the three of our abstract states that matter!

What we could do at this point is build up another (much smaller!) transition matrix for

our simplified Markov chain, but our previous considerations might suggest us another smarter way

to proceed.

In fact, you may have noticed that if the particle starts in abstract

state $2$, no matter what (abstract) state the particle visits in the next step, after two steps it will be

again in abstract state $2$. If the particle start from abstract states $1$ and $3$, after one step it will lie in

abstract state $2$ and so happens after an odd number of steps. The only possibility for the particle to be

in abstract state $3$ after

three steps is to start from abstract state $2$ (and this happens with probability $\frac{4}{9}$); conditioning on that, the probability

that at the third step the particle will move from state $2$ to state $3$ is $\frac{1}{3}$, so that overall I have a probability

\(\frac{1}{3}\cdot\frac{4}{9}=\frac{4}{27}\)

Therefore, we reached the same conclusion as before in a much more “elegant” way.